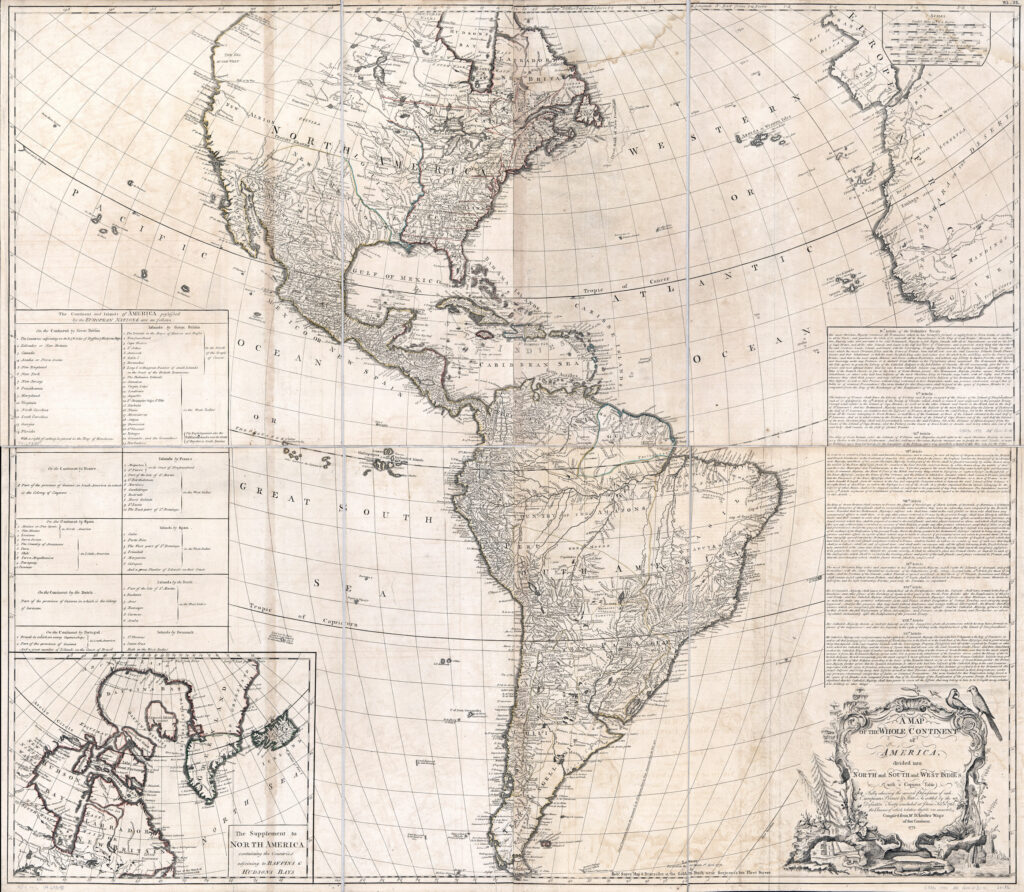

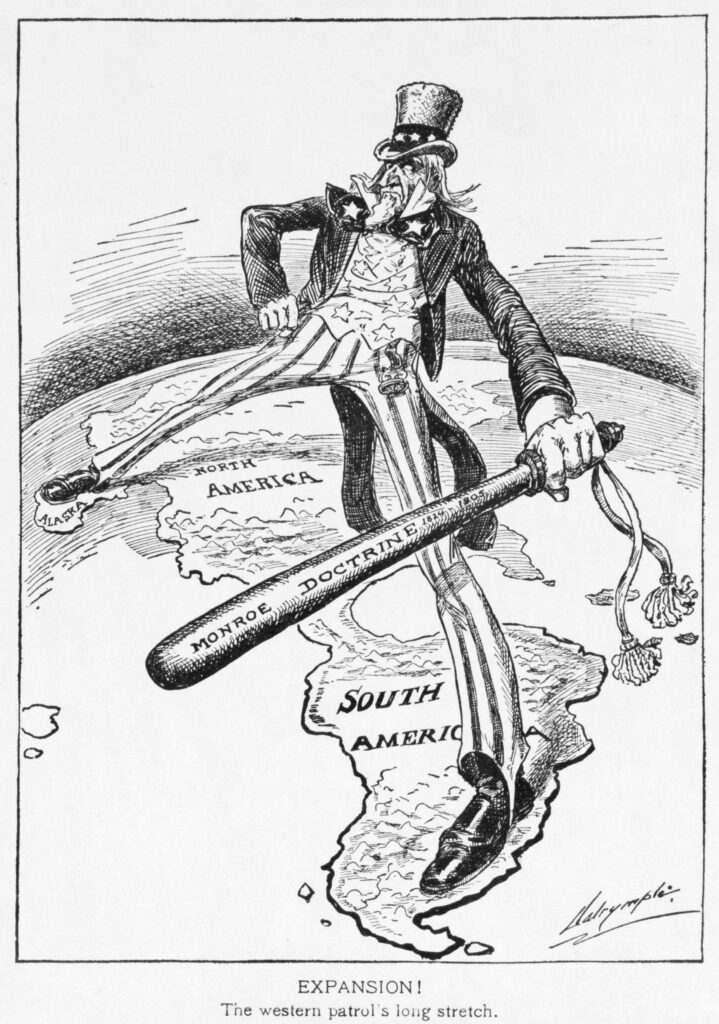

In 1823, President Monroe gave a speech before Congress. Part of this speech became the Monroe Doctrine: a U.S. foreign policy framework about the Western Hemisphere. This framework would affect relations with newly independent Latin American nations for years to come.

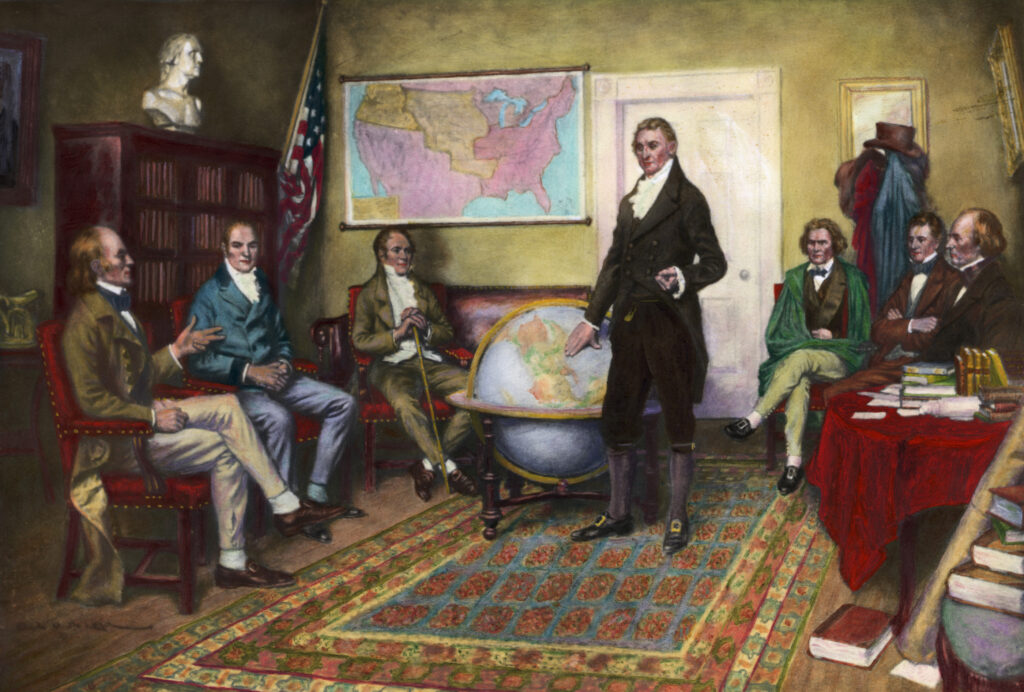

The Monroe Doctrine is a U.S. foreign policy framework addressing America’s security and commercial interests in the Western Hemisphere. It emerged from three paragraphs in President James Monroe’s annual address before the U.S. Congress on December 2, 1823. The doctrine addresses how the United States would conduct foreign relations with newly independent nations in Central and South America and how to curb European ambitions in Western Hemisphere territories.

President Monroe gave the speech in person before Congress and handed out written copies to senators and representatives afterward. However, Monroe intended for the message to reach the American people.

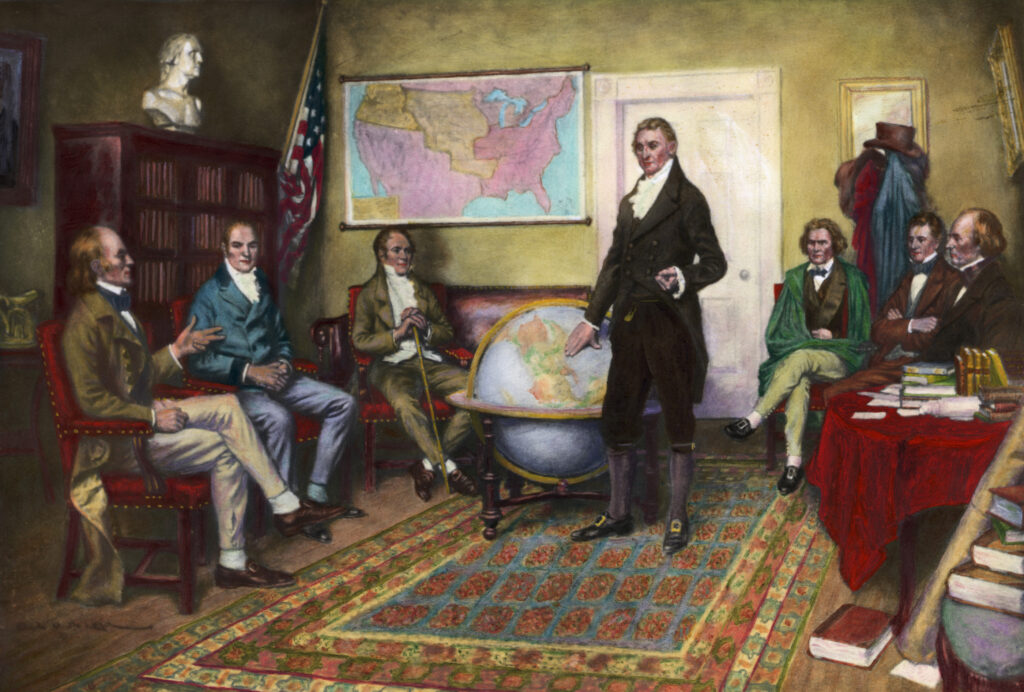

The statement had much to do with the independence of the United States itself. The Spanish monarchy had controlled trade in its Latin American empire through a mercantilist system—restricting and controlling trade to benefit the empire. This system was used throughout the monarchies in Europe and was one of the reasons the American colonies rebelled against Great Britain in 1776. The American colonies wanted to engage independently in free trade. The same was true of the newly independent Latin American nations, which could now openly trade with the United States. Great Britain shared this concern. Its Foreign Minister, George Canning, offered to issue a joint statement with the Americans against recolonization in the Americas. Monroe received advice from many senior statesmen, including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who urged him to accept the proposal. In the end, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams persuaded Monroe to issue an independent statement. He argued that issuing an independent foreign policy statement equated to the independence of the United States itself, free to conduct its foreign affairs without influence from other nations.

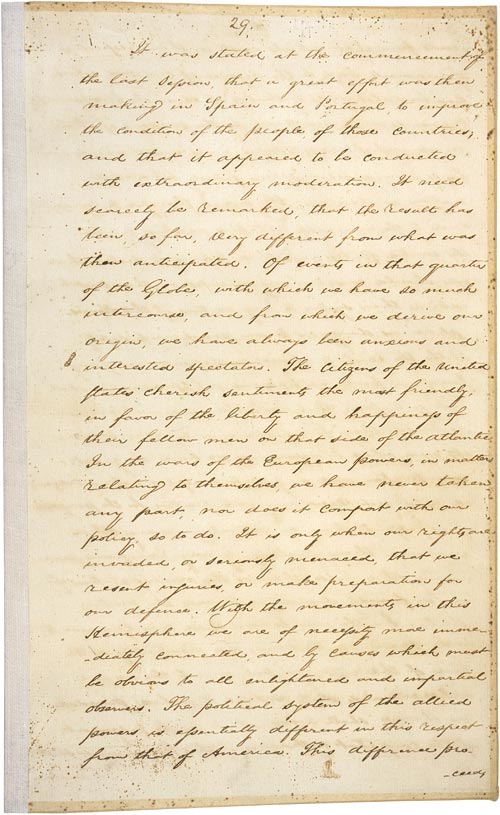

Between 1810 and 1822, fifteen Latin American colonies declared independence from the Spanish empire; ten alone between 1821 and 1822. Unsure of their ability to maintain independent democratic governments, Monroe’s administration hesitated to recognize these new nations. Anti-Catholic sentiment also ran high in the United States. Some government officials argued that democracy could not survive under the Pope’s perceived influence over the people. But hesitation in recognizing new nations did not stop Monroe from issuing his statement against the threat of recolonization. If European powers conquered these republics, the United States’ new commercial ties would be lost. Also, the center of power would again revert back to Europe. The Americans would again be in the position of having to negotiate with the European power, rather than the people. Since empires are built on exploitation and suppressing individual liberties, the U.S. government shuddered at the thought of that influence once again at America’s doorstep. Empires are expensive to maintain and require a strong military to guard their interests, which also could present a threat to national security.

Yes, but not immediately. The United States had dispatched Joel Roberts Poinsett to Chile in 1811 to gather intelligence about regional independence movements. It was not until early 1824 that Monroe sent diplomats to other new nations after making the foreign policy remarks in his December 1823 address. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams gave these diplomats specific instructions on how they should follow Monroe’s policies.

U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian; Monroe Doctrine, 1823 Nicholas Guyatt, “The Adams Doctrine and an “Empire of States,” Diplomatic History, Vol. 47, Issue 5, November 2023, pp. 823-844. Jay Sexton, The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012).

Do you have an item that you feel would be at home in our collections? The National Museum of American Diplomacy is always looking for new additions and would love to hear from you. Help us tell the stories of diplomacy and contact us about donating your object. Our curatorial team will be in touch.

Sign up for our Newsletter

Sign up to receive our monthly newsletter, special invitations to events hosted by the museum, or free learning resources for educators and students in your inbox.